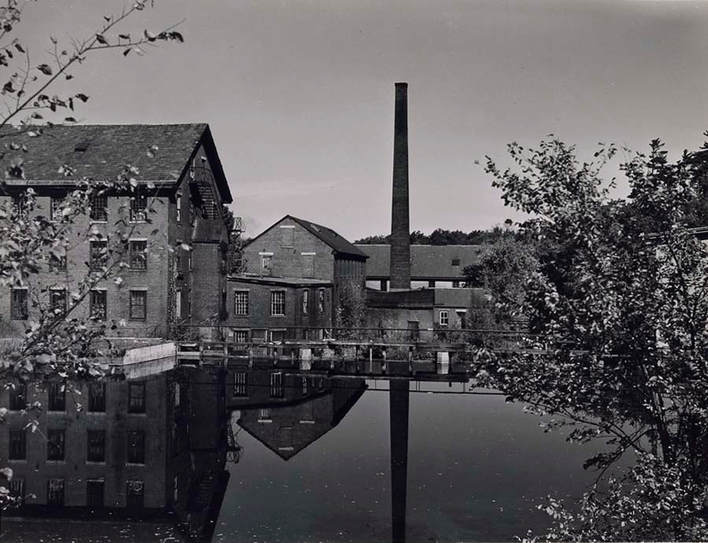

Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Ballardvale Mill buildings, distant view with reflections, gelatin silver print, c. 1946. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA, gift of Saundra B. Lane in honor of Jock Reynolds, 1998.169. Image Credit: (c) The Lane Collection.

Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Ballardvale Mill buildings, distant view with reflections, gelatin silver print, c. 1946. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA, gift of Saundra B. Lane in honor of Jock Reynolds, 1998.169. Image Credit: (c) The Lane Collection.  New England Irrelevancies, oil on canvas, 1953. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of William H. and Saundra B. Lane and Henry H. and Zoe Oliver Sherman Fund.

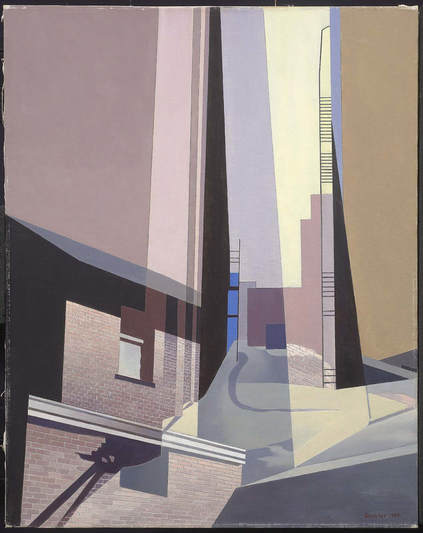

New England Irrelevancies, oil on canvas, 1953. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of William H. and Saundra B. Lane and Henry H. and Zoe Oliver Sherman Fund. In 1946 Charles Sheeler lived for six weeks in Andover as the guest of Phillips Academy. As the school's first artist-in-residence*, he was free to roam the town, uninhibited by any obligation, including that of teaching. Quickly he found his way to one of the industrially picturesque, former mill sections of Andover, a little cluster of red brick buildings and working-class clapboard houses alongside the Shawsheen River. Today as then it was known as Ballardvale. There he made drawings and took photographs that inspired him to create artworks that continued his exploration of American values through depictions of our industrial architecture.

On a recent afternoon visit to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, I went to a gallery where I knew I would find one of those artworks, New England Irrelevancies, an oil on canvas completed by Sheeler in 1953. A kind of double exposure, it is composed of images of Ballardvale mills combined with ones Sheeler studied in Manchester, New Hampshire, during another artist-in-residency, at the Currier Museum of Art in 1948. In an interview tape-recorded by the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art on June 18, 1959, Sheeler offered a somewhat clumsy but convincing explanation of his personal philosophy of perception that lay behind this technique. "I realized that, when we look at any object around us and [walk] around among other things subsequently, we have to bring it up into a conscious plane," he said. That's "because -- at least I didn't realize it or think of it in that light for some time -- but when we look at the next thing in sequence to the first object that we have gazed at, there's still an overtone carried over of what the retina has just previously recorded. And in these later pictures, I make use of that as an element in the final picture. There may be two such images playing against each other or possibly three, no definite number arbitrarily decided, but certainly two."

I like this as a way of explaining how perception works for everyone, not just artists, and why our memories sometimes (often?) get distorted. I also like the way it helps me appreciate this painting more than I initially did. And if I needed the artist's words to get there, so be it, Tom Wolfe.

The MFA curators who wrote the online catalog description of New England Irrelevancies speculate that Sheeler may have been unconsciously speaking of himself when he chose his title. Presuming that it alluded to "the once-impressive buildings and prosperous industries that had dominated Andover and Manchester but were now obsolete," they conjectured that the "sense of the buildings' irrelevance may have struck Sheeler personally, too: by the time he completed this painting, he was seventy years old and remote from the artistic mainstream."

It is true that the abstract expressionists were in the ascendancy in 1953. But after having "bailed out" (his words) for a ten-year period beginning in 1909, abandoning what he had been doing artistically up until then, Sheeler was confident he had found his proper path. That's not to say he liked what he was eventually label: Precisionist. Nor did he like being called a Realist -- a meaningless term, when one considers the nature of reality.

"I do like contrasts." That's as far as he was willing to go with defining himself for his Smithsonian interviewer. "I think they're important; that's an important consideration to me. It may be contrasts of forms or of color. I like a black, not as a rule, but at times I like a black coming right next to a white, kind of like a pistol shot in the still air."

To be continued.

*Some of the more recent artists-in-residence at P.A.: Frank Stella, Robert Frank, Kerry James Marshall, Dawoud Bey, Trisha Brown, Fred Wilson, Wendy Ewald, and William Wegman.

On a recent afternoon visit to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, I went to a gallery where I knew I would find one of those artworks, New England Irrelevancies, an oil on canvas completed by Sheeler in 1953. A kind of double exposure, it is composed of images of Ballardvale mills combined with ones Sheeler studied in Manchester, New Hampshire, during another artist-in-residency, at the Currier Museum of Art in 1948. In an interview tape-recorded by the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art on June 18, 1959, Sheeler offered a somewhat clumsy but convincing explanation of his personal philosophy of perception that lay behind this technique. "I realized that, when we look at any object around us and [walk] around among other things subsequently, we have to bring it up into a conscious plane," he said. That's "because -- at least I didn't realize it or think of it in that light for some time -- but when we look at the next thing in sequence to the first object that we have gazed at, there's still an overtone carried over of what the retina has just previously recorded. And in these later pictures, I make use of that as an element in the final picture. There may be two such images playing against each other or possibly three, no definite number arbitrarily decided, but certainly two."

I like this as a way of explaining how perception works for everyone, not just artists, and why our memories sometimes (often?) get distorted. I also like the way it helps me appreciate this painting more than I initially did. And if I needed the artist's words to get there, so be it, Tom Wolfe.

The MFA curators who wrote the online catalog description of New England Irrelevancies speculate that Sheeler may have been unconsciously speaking of himself when he chose his title. Presuming that it alluded to "the once-impressive buildings and prosperous industries that had dominated Andover and Manchester but were now obsolete," they conjectured that the "sense of the buildings' irrelevance may have struck Sheeler personally, too: by the time he completed this painting, he was seventy years old and remote from the artistic mainstream."

It is true that the abstract expressionists were in the ascendancy in 1953. But after having "bailed out" (his words) for a ten-year period beginning in 1909, abandoning what he had been doing artistically up until then, Sheeler was confident he had found his proper path. That's not to say he liked what he was eventually label: Precisionist. Nor did he like being called a Realist -- a meaningless term, when one considers the nature of reality.

"I do like contrasts." That's as far as he was willing to go with defining himself for his Smithsonian interviewer. "I think they're important; that's an important consideration to me. It may be contrasts of forms or of color. I like a black, not as a rule, but at times I like a black coming right next to a white, kind of like a pistol shot in the still air."

To be continued.

*Some of the more recent artists-in-residence at P.A.: Frank Stella, Robert Frank, Kerry James Marshall, Dawoud Bey, Trisha Brown, Fred Wilson, Wendy Ewald, and William Wegman.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed