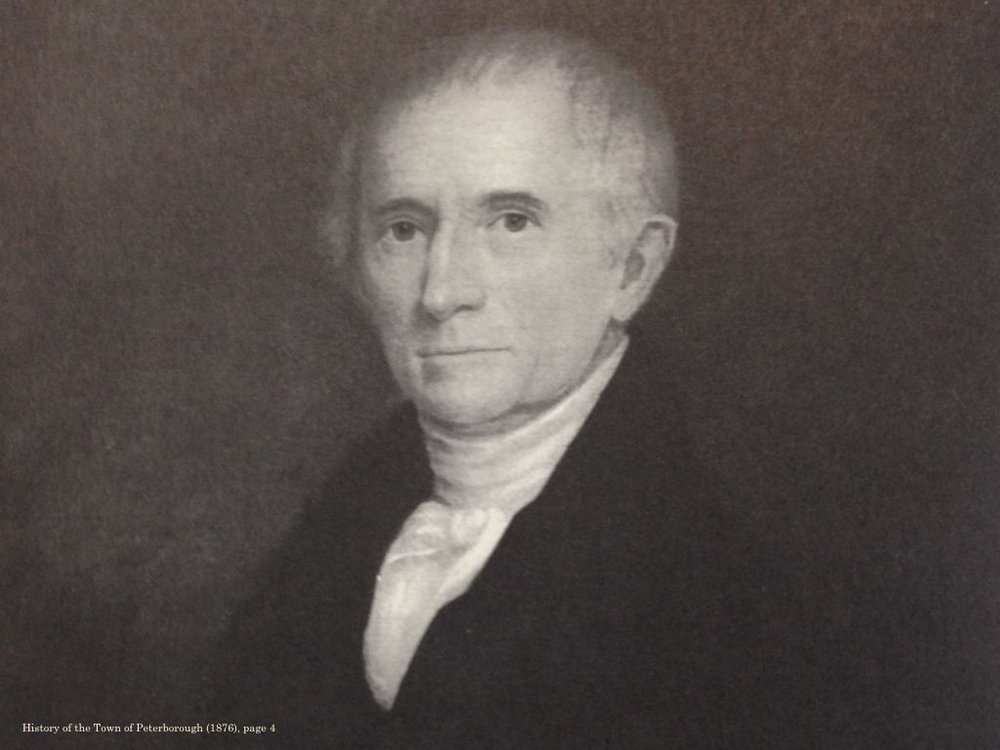

Are you feeling about yet another dead white male making an appearance in these Commentaries the same way I am feeling? He is Abiel Abbot (1765-1859), Harvard class of 1787, an eventual doctor of divinity, who wrote the book I am now reading, History of Andover From Its Settlement to 1829, published in Andover in 1829, so for him, it was an up-to-date compilation. (He calls himself "The Compiler" of the book, not its author, because he "used with much freedom, the language of the documents from which the compilation has been made.") Aside from my inability to think of him as a "real" person, I am distracted by his contemporary perspective. For example, he writes, of the "Indians": "It was important to our ancestors, that peace was preserved with the natives for so many years. There was no war with them near Andover for more than thirty years after the plantation was begun [in 1642]; but they were obliged to attend to military duty and to be equipped. How easily might the first settlers of New England have been destroyed, had the natives been hostile, and had they combined and exerted themselves to remove their neighbours! Divine providence favored the arduous undertaking of settling a wilderness. The first planters were men of principle, and treated the savages with kindness and justice, and secured their confidence." He continues: "When wars commenced, the planters had increased in numbers and strength, and, with their superior skill and means of defence, they were able to protect themselves, and drive the enemy to different parts, or weaken and destroy them, and compel them to preserve peace."

As Reverend Abbot describes it, in those earliest years of white settlement, the Merrimack was teeming with fish and the forest filled with game. "The [native] inhabitants were able safely and quietly to pursue their business..." But some thirty years later, by his own account things had changed. After a single generation, although he doesn't state it, the colonists had begun to encroach upon the natives' way of life. What he does say is that they rebelled, they fought, and lost. "It is probable, that the Indians left Andover, at the commencement of Philip's war [1675], and that few, if any, families have resided there since. The residence of an Indian family in Andover is not now recollected by the oldest inhabitants."

Actually, according to Claude M. Fuess's history of Andover, there was a direct Indian attack on Andover in 1676, on April 8th, to be exact. In recounting those so-called Indian Wars of 1676, Fuess calls the Native Americans “savages” (Fuess, Andover: Symbol of New England, p. 70); “red men” (p. 73); and “copper-colored inhabitants” (p. 11). Likewise, Abiel Abbot's is, of course, in every way an account from the perspective of himself. There is no attempt at seeing the town's history from any other point of view. And yet I need to read it to learn about the early days of the colonists in the place they named Andover. And so I hold it at arms' length and read on, trying to accept the reverend as someone who isn't a caricature, someone I probably would have agreed with, and commiserated with, if I had been born in his time and place instead of mine. The exercise is part of my attempt at trying to accept and understand people who don't agree with me today. They too strike me as caricatures, but the fact is, they are real -- as real as Abiel Abbot once was.

To be continued.

As Reverend Abbot describes it, in those earliest years of white settlement, the Merrimack was teeming with fish and the forest filled with game. "The [native] inhabitants were able safely and quietly to pursue their business..." But some thirty years later, by his own account things had changed. After a single generation, although he doesn't state it, the colonists had begun to encroach upon the natives' way of life. What he does say is that they rebelled, they fought, and lost. "It is probable, that the Indians left Andover, at the commencement of Philip's war [1675], and that few, if any, families have resided there since. The residence of an Indian family in Andover is not now recollected by the oldest inhabitants."

Actually, according to Claude M. Fuess's history of Andover, there was a direct Indian attack on Andover in 1676, on April 8th, to be exact. In recounting those so-called Indian Wars of 1676, Fuess calls the Native Americans “savages” (Fuess, Andover: Symbol of New England, p. 70); “red men” (p. 73); and “copper-colored inhabitants” (p. 11). Likewise, Abiel Abbot's is, of course, in every way an account from the perspective of himself. There is no attempt at seeing the town's history from any other point of view. And yet I need to read it to learn about the early days of the colonists in the place they named Andover. And so I hold it at arms' length and read on, trying to accept the reverend as someone who isn't a caricature, someone I probably would have agreed with, and commiserated with, if I had been born in his time and place instead of mine. The exercise is part of my attempt at trying to accept and understand people who don't agree with me today. They too strike me as caricatures, but the fact is, they are real -- as real as Abiel Abbot once was.

To be continued.

According to both Fuess (whose grave at P.A. is pictured here) and Abbot, a Native American named Cutshamache sold the land we now call Andover to the town's founders sometime prior to 1646, the year of incorporation. The price was 6 pounds and a coat. But Fuess probably got the detail from Abbot. (Fuess, Andover: Symbol of New England, 1959, p. 29), (Abbot, History of Andover, 1829, p. 11).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed