I like to think of Phillips Academy as a place where good values reign -- and they mostly do. Yet when an exquisite, eighteenth-century needlework hanging on the wall of its Addison Gallery of American Art was discovered to have been stolen property, P.A. as much as said "tough luck" to its rightful owner.

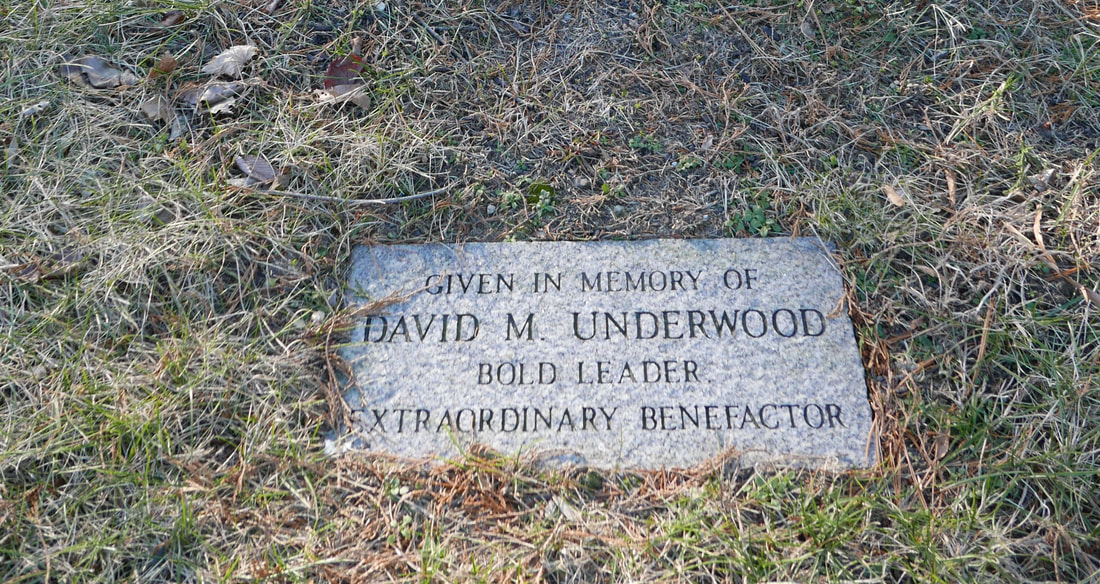

I was reminded of this incident of more than twenty years ago when, while walking through the cemetery at P.A. on Christmas Day, I came upon a plaque under a tree planted in honor of board of trustees member David M. Underwood (1937-2015), P.A. class of ’54. It was he who donated the $32,200 that P.A. paid for the purloined piece at a Sotheby's sale in New York on October 22, 1994. The object was attractive to P.A. not only for its beauty and workmanship but also because it had been executed by Hannah Phillips (1742-1764), a member of the family that founded P.A. in 1778. Indeed, she was the elder sister of Samuel Phillips (1752-1802).

It perhaps goes without saying that neither P.A. nor Sotheby's knew the needlework had been stolen when it changed hands. Nor had the theft been reported. W.G. Brooks Thomas (1925-2008) had assumed it to have been destroyed when his house, in Jamestown, Rhode Island, burned down in 1986 in a suspected arson blaze so severe that six firefighters were injured doing battle with it. But once he was made aware of its continued existence, there was no doubt it was the one his father, C. Lloyd Thomas (P.A., class of 1914), bequeathed to him upon his death in 1982. In turn, the elder Thomas had received it in a bequest. The Thomases are related to the Phillipses.

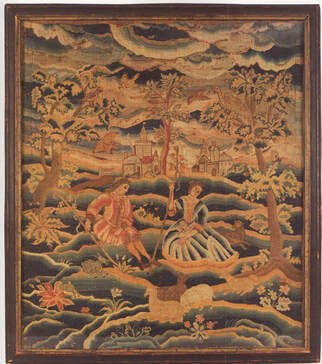

Known as The Shepherdess, the needlework depicts a woman seated in a fanciful landscape surrounded by animal figures, including lambs and rabbits. A fellow sheepherder, presumed to be wooing her, is seated by her side. Each has a shepherd’s crook in hand. Clouds, birds, butterflies, and two architectural structures, one of which appears to be a church, complete the picture. Its colors are teal blue, rose pink, golden beige, and brown. The provenance given in the Sotheby's catalog says it was descended in the Phillips family to a "C. Thomas Lloyd" -- obviously a typo, a transposition, and a main reason why no one in the Thomas family was alerted to it at the time of the sale. The Sotheby's provenance states further that it went next to an antiques dealer, William Taylor of Attleboro, Massachusetts. That part is accurate. Mr. Taylor was in fact the one who sold it to Nina Fletcher Little (1903-1993), a renowned, early American folk art collector and scholar — a pioneer in the field — whose collection was sold by Sotheby’s in two landmark sales. P.A. bought the needlework at the first one.

That the needlework resurfaced after the Thomas house and its contents went up in flames wasn’t a complete surprise. A few years after the fire, Jamestown police recognized some of the Thomas property on a list of seized items circulated by police in a nearby community, South Dartmouth, Massachusetts, whereupon Mr. Thomas recovered a painting, a chandelier, and a few other antique objects. However, he didn’t learn the whereabouts of the needlework until 1995, when Betty Ring (1923-2014), a textile scholar doing work on a catalog for the Addison, alerted him to it. She had been commissioned to write about both The Shepherdess and another needlework, given to the Addison by the elder Thomas in 1962. It was then that the true provenance of The Shepherdess was understood.

Mr. Thomas thought it would be a simple thing to have the property, his property, returned to him, especially after being reassured by a lawyer for the Little estate. But soon enough, a different lawyer began to communicate with him and it seemed it wasn't going to be so simple after all. And so, on a Wednesday afternoon, May 29, 1996, Mr. Thomas and his wife drove up from Rhode Island to Andover and, with photographs, insurance lists, and other proof of ownership at the ready, walked into the gallery to claim it. "We finally wound up standing in front of our Hannah Phillips needlework hanging on the wall," he wrote in a letter to the editor of Maine Antique Digest. With them were the Addison's security chief, its director of museum resources, B.J. Larson, and Andover police detective James E. Haggerty. "Detective Haggerty left with us saying he thought he'd have it back for us in a week," Mr. Thomas's letter continued, "and we understood Larson would take the matter up with [gallery director] Mr. [Jock] Reynolds upon the latter's return." But Detective Haggerty called them a week later with bad news. He could do nothing for them. They heard nothing from the gallery or from P.A. itself. So on July 12, 1996, the Thomases wrote to head of school Barbara Landis Chase in whose honor the needlework had been bought in the first place. To be fair, it was the Thomases' first, direct communication with P.A. about the matter. But P.A. took its time in responding. "We finally received a letter back from her dated August 9, 1996," said Mr. Thomas, who recounted that "Ms. Chase, while being oh-so-sympathetic about our loss and wanting to talk to us, made a written statement, viz., 'After having consulted counsel, it is our belief that the Addison came into possession of the Shepherdess lawfully and that it is entitled to retain possession of the needlework.'"

Say wha'? Finders keepers? Mr. Thomas thought not, and by the following November, his M.A.D. letter states, "my lawyer straightened the Gallery and the school out on the law and obtained the return of the needlework. Sorry, Andover, it was stolen from me and you are not entitled to keep stolen goods.

"I still think the school should pay my legal bills...," Mr. Thomas opines in conclusion. "The needlework came down through my Phillips ancestors to me. It was stolen, and I got it back. It cost me legal fees I should never have had to pay. End of story."

It is not known if Andover moved against Sotheby's, the auction house against the Little estate, the estate against the dealer, and the dealer against whomever he bought the needlework from. But a good guess is that none of these parties did so. Otherwise, these actions surely would have been reported in M.A.D. by staff or by Constance Lowenthal, executive director of the International Foundation for Art Research, who initially brought the story to M.A.D.'s attention. It is presumed, then, that the thief or thieves got away with it. But at least P.A. didn't.

I was reminded of this incident of more than twenty years ago when, while walking through the cemetery at P.A. on Christmas Day, I came upon a plaque under a tree planted in honor of board of trustees member David M. Underwood (1937-2015), P.A. class of ’54. It was he who donated the $32,200 that P.A. paid for the purloined piece at a Sotheby's sale in New York on October 22, 1994. The object was attractive to P.A. not only for its beauty and workmanship but also because it had been executed by Hannah Phillips (1742-1764), a member of the family that founded P.A. in 1778. Indeed, she was the elder sister of Samuel Phillips (1752-1802).

It perhaps goes without saying that neither P.A. nor Sotheby's knew the needlework had been stolen when it changed hands. Nor had the theft been reported. W.G. Brooks Thomas (1925-2008) had assumed it to have been destroyed when his house, in Jamestown, Rhode Island, burned down in 1986 in a suspected arson blaze so severe that six firefighters were injured doing battle with it. But once he was made aware of its continued existence, there was no doubt it was the one his father, C. Lloyd Thomas (P.A., class of 1914), bequeathed to him upon his death in 1982. In turn, the elder Thomas had received it in a bequest. The Thomases are related to the Phillipses.

Known as The Shepherdess, the needlework depicts a woman seated in a fanciful landscape surrounded by animal figures, including lambs and rabbits. A fellow sheepherder, presumed to be wooing her, is seated by her side. Each has a shepherd’s crook in hand. Clouds, birds, butterflies, and two architectural structures, one of which appears to be a church, complete the picture. Its colors are teal blue, rose pink, golden beige, and brown. The provenance given in the Sotheby's catalog says it was descended in the Phillips family to a "C. Thomas Lloyd" -- obviously a typo, a transposition, and a main reason why no one in the Thomas family was alerted to it at the time of the sale. The Sotheby's provenance states further that it went next to an antiques dealer, William Taylor of Attleboro, Massachusetts. That part is accurate. Mr. Taylor was in fact the one who sold it to Nina Fletcher Little (1903-1993), a renowned, early American folk art collector and scholar — a pioneer in the field — whose collection was sold by Sotheby’s in two landmark sales. P.A. bought the needlework at the first one.

That the needlework resurfaced after the Thomas house and its contents went up in flames wasn’t a complete surprise. A few years after the fire, Jamestown police recognized some of the Thomas property on a list of seized items circulated by police in a nearby community, South Dartmouth, Massachusetts, whereupon Mr. Thomas recovered a painting, a chandelier, and a few other antique objects. However, he didn’t learn the whereabouts of the needlework until 1995, when Betty Ring (1923-2014), a textile scholar doing work on a catalog for the Addison, alerted him to it. She had been commissioned to write about both The Shepherdess and another needlework, given to the Addison by the elder Thomas in 1962. It was then that the true provenance of The Shepherdess was understood.

Mr. Thomas thought it would be a simple thing to have the property, his property, returned to him, especially after being reassured by a lawyer for the Little estate. But soon enough, a different lawyer began to communicate with him and it seemed it wasn't going to be so simple after all. And so, on a Wednesday afternoon, May 29, 1996, Mr. Thomas and his wife drove up from Rhode Island to Andover and, with photographs, insurance lists, and other proof of ownership at the ready, walked into the gallery to claim it. "We finally wound up standing in front of our Hannah Phillips needlework hanging on the wall," he wrote in a letter to the editor of Maine Antique Digest. With them were the Addison's security chief, its director of museum resources, B.J. Larson, and Andover police detective James E. Haggerty. "Detective Haggerty left with us saying he thought he'd have it back for us in a week," Mr. Thomas's letter continued, "and we understood Larson would take the matter up with [gallery director] Mr. [Jock] Reynolds upon the latter's return." But Detective Haggerty called them a week later with bad news. He could do nothing for them. They heard nothing from the gallery or from P.A. itself. So on July 12, 1996, the Thomases wrote to head of school Barbara Landis Chase in whose honor the needlework had been bought in the first place. To be fair, it was the Thomases' first, direct communication with P.A. about the matter. But P.A. took its time in responding. "We finally received a letter back from her dated August 9, 1996," said Mr. Thomas, who recounted that "Ms. Chase, while being oh-so-sympathetic about our loss and wanting to talk to us, made a written statement, viz., 'After having consulted counsel, it is our belief that the Addison came into possession of the Shepherdess lawfully and that it is entitled to retain possession of the needlework.'"

Say wha'? Finders keepers? Mr. Thomas thought not, and by the following November, his M.A.D. letter states, "my lawyer straightened the Gallery and the school out on the law and obtained the return of the needlework. Sorry, Andover, it was stolen from me and you are not entitled to keep stolen goods.

"I still think the school should pay my legal bills...," Mr. Thomas opines in conclusion. "The needlework came down through my Phillips ancestors to me. It was stolen, and I got it back. It cost me legal fees I should never have had to pay. End of story."

It is not known if Andover moved against Sotheby's, the auction house against the Little estate, the estate against the dealer, and the dealer against whomever he bought the needlework from. But a good guess is that none of these parties did so. Otherwise, these actions surely would have been reported in M.A.D. by staff or by Constance Lowenthal, executive director of the International Foundation for Art Research, who initially brought the story to M.A.D.'s attention. It is presumed, then, that the thief or thieves got away with it. But at least P.A. didn't.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed