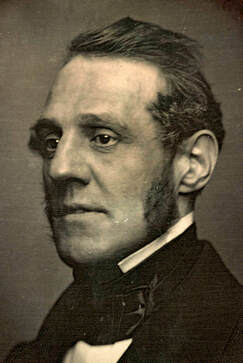

George Thompson

George Thompson Marion La Mere’s research on the Underground Railroad was a W.P.A. project designed to document actual routes. “…I gather chiefly what ‘grandmother told Aunt Sarah, etc.’ and don't rely on that. The facts I set down are documented,” she wrote on November 25, 1934, to Wilbur H. Siebert, who was doing similar research as part of his academic work at Ohio State University. In an aside, Miss La Mere said: "I assume that you are quite aware of the peculiar situation in Andover during the score of years prior to the Civil War — when the Andover Theological Seminary on 'The Hill' dominated the town — and upheld the Fugitive Slave Law." To learn more about the seminary's pro-slavery stance, she suggested he read The Pioneer Preacher, autobiography of Sherlock Bristol (1815-1906), who attended Andover's Phillips Academy.*

I took Miss La Mere's advice myself and found a copy of the book, published in 1887. In the pertinent chapter Bristol described a nasty situation that arose one night in 1835, when George Thompson, the famous British abolitionist, was invited to speak at Andover's Methodist church. "A mob had just driven him from Boston," Bristol recounted, but Thompson was no safer in Andover, where it was "boldly given out that a mob would break up the meeting and probably tar and feather [him]." Bristol and about fifty other students, all anti-slavery advocates, stood guard, armed with clubs. Like Bristol, most of them were farmers' sons, looking quite able to wield their weapons. "I imagine the mobocratic portion of the audience studied us rather carefully," Bristol said. Nonetheless, it did pounce. When the two-hour oration ended, "in an instant every light was blown out, and the mob rushed for the pulpit." Still, Bristol and his group prevailed, "with clubs brandished so threateningly that the mob kept at respectful distance and finally dispersed." That wasn't the end of it, however. Bristol and the others spent the night guarding Thompson and the Methodist minister who had accommodated him, saving them from being attacked by "a hundred students dashing down from Andover hill at a two-forty pace." That was a victory for the anti-slavery movement, but not, alas, for Bristol, who was questioned and expelled along with one other student. (Sixty others left P.A. of their own accord.) He sold his books to pay his debts and sought work among Andover's farmers. They were reluctant to hire "a fanatic," but a member of the Holt family took a chance. Holt "talked in the stores and taverns about his expelled student, his strength and skill in farming." Lawyers offered him money to study law, but Bristol had his heart set on preaching "the law of God." Then Frye Village businessman and abolitionist John Smith and some of his business partners gave Bristol $150 and sent him off to Oberlin College, whose reputation as a “manufactory of fanatics," due to its anti-slavery activities, was growing apace.

To be continued.

*The two schools together occupied "The Hill," short for "Academy Hill," in Andover from 1807, when Andover Theological Seminary was founded, until 1908, when it moved to Harvard's campus. In 1931, it became affiliated with Newton Theological Institution of Newton, Massachusetts. In 1965, they were merged to form Andover Newton Theological School.

I took Miss La Mere's advice myself and found a copy of the book, published in 1887. In the pertinent chapter Bristol described a nasty situation that arose one night in 1835, when George Thompson, the famous British abolitionist, was invited to speak at Andover's Methodist church. "A mob had just driven him from Boston," Bristol recounted, but Thompson was no safer in Andover, where it was "boldly given out that a mob would break up the meeting and probably tar and feather [him]." Bristol and about fifty other students, all anti-slavery advocates, stood guard, armed with clubs. Like Bristol, most of them were farmers' sons, looking quite able to wield their weapons. "I imagine the mobocratic portion of the audience studied us rather carefully," Bristol said. Nonetheless, it did pounce. When the two-hour oration ended, "in an instant every light was blown out, and the mob rushed for the pulpit." Still, Bristol and his group prevailed, "with clubs brandished so threateningly that the mob kept at respectful distance and finally dispersed." That wasn't the end of it, however. Bristol and the others spent the night guarding Thompson and the Methodist minister who had accommodated him, saving them from being attacked by "a hundred students dashing down from Andover hill at a two-forty pace." That was a victory for the anti-slavery movement, but not, alas, for Bristol, who was questioned and expelled along with one other student. (Sixty others left P.A. of their own accord.) He sold his books to pay his debts and sought work among Andover's farmers. They were reluctant to hire "a fanatic," but a member of the Holt family took a chance. Holt "talked in the stores and taverns about his expelled student, his strength and skill in farming." Lawyers offered him money to study law, but Bristol had his heart set on preaching "the law of God." Then Frye Village businessman and abolitionist John Smith and some of his business partners gave Bristol $150 and sent him off to Oberlin College, whose reputation as a “manufactory of fanatics," due to its anti-slavery activities, was growing apace.

To be continued.

*The two schools together occupied "The Hill," short for "Academy Hill," in Andover from 1807, when Andover Theological Seminary was founded, until 1908, when it moved to Harvard's campus. In 1931, it became affiliated with Newton Theological Institution of Newton, Massachusetts. In 1965, they were merged to form Andover Newton Theological School.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed