“Where are the young people?” We often hear that plaintive cry when an antique-show or auction is mostly populated, as it usually is, with representatives of the older demographic groups. Well, I have a good idea of where the younger ones are. They’re at South By Southwest , the annual music, film, and interactive conference and festival held in Austin, Texas. They’re at TED conferences, where “Technology, Entertainment, and Design” converge. They’re at Comic-Con in San Diego. They’re definitely at hacker conventions, one of which, ToorCon, I attended as a reporter for another paper and where I interviewed its then 17-year-old white-hat hacker cofounder and many of his highly intelligent colleagues. (See "H is for Hacker.")

I bring this up, because if there’s any hope of attracting more than a trickle of new collectors to the delights of old things, I believe one way is through the portals of antique science and technology, especially antique photography. Where else are the young people? Wherever they may be, surely you have noticed, they’re creating images -- photographs -- billions of them, with their phones and other devices. Don’t you think some might be just a little bit curious about the imagery and image-making processes of the past? It’s my opinion that many more of them, if given the choice, would display a far greater interest in those things than in, say, the carving of an acanthus leaf on the knee of a cabriole leg.

The leadoff essayists in this well produced volume are Jack and Beverly Wilgus, who collect camera obscuras and objects and images associated with camera obscuras -- i.e., the optical devices that take advantage of a phenomenon of nature in order to project an upside-down image of reality on a wall, screen, or smaller surface. These self-styled “guardians and champions” of the camera obscura’s history have also become “designers and builders” of several box camera obscuras and a small tent camera obscura that they call “The Magic Mirror of Life.” What is more, they collect “camera obscura experiences,” traveling around the country and the world to visit other working examples. How fun is that? Who wouldn’t want to join them? It’s one of my beliefs that young people are adept at collecting intangible things, like experiences. What if they were introduced to yet another kind?

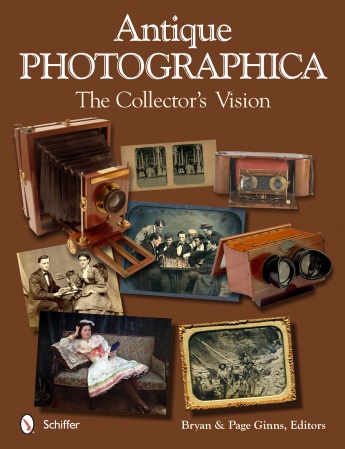

Like the Wilguses, Ralph and Bobbie London are a collecting couple, but in the Londons’ case, each has contributed a separate chapter. The beauty of wood and brass is on display in the images of Ralph’s 19th-century American camera collection. There are, for example, a circa 1845 quarter-plate daguerreotype camera labeled “John Roberts, Boston” and circa 1890 full-plate daguerreotype Star View camera in mahogany. He hasn’t stopped there, however. This collecting area has allowed him to hunt for the more elusive posing chairs, head clamps, and photographic-chemical bottles, along with such things as “brass birdies,” used to keep children of earlier generations occupied while they were having their pictures taken. Ralph describes how one from his collection works: “Partially filling the base of the device with water and squeezing the bulb on the tube makes the bird sing while moving its mouth and tail.”

Bobbi’s chapter is on Stanhopes, also called “peeps,” which are microscopic image-viewing devices. As Bobbi writes, the term is “used to refer both to the combination lens-image unit and to the items into which they were placed.” My use of the term “microscopic” is not hyperbolical: the images are less than 1/30 of an inch square. (The diameter of a typical eye’s pupil is 1/6 of an inch.) As for the lenses, they are small enough to fit into an array of objects, large and small, that only imagination has limited. Developed by René Prudent Patrice Dagron (1819-1900) of France, the novelties were popular from the late 19th century into the 20th. They are the namesake of the lens’s inventor, Britain’s Charles Stanhope (1753-1816). The illustrations from Bobbi’s collection include Stanhope jewelry, letter openers, pipes, pencils, knitting-needle nibs, scent bottles, watch fobs, rosary beads, and children’s items, one of which is a miniature potty seat carved of bone. Humor and whimsy these Stanhope creators certainly had.

Leonard A. Walle’s chapter on American ambrotypes offers nearly 20 pages of rich visuals and commentary on the so-called “daguerreotypes on glass,” whose period of popularity was a veritable sliver of time, 1857-1858. “Hunter with His Dog” shows a contemplative man posed with his gun, game bag, traps, and long-eared canine seated obediently beside him against a painted backdrop. “Franklin Hose Co. No 5 Utica NY” presents a group portrait of ten uniformed firefighters along with tools of their trade, including the company’s hose nozzle, two trumpets, an oil torch, and hose wrenches. One of the group looks like a kid. He was indeed “torch boy” James McNall, named, as are all of them, courtesy of the Utica Tribune. Ambrotypes, which made use of the wet-collodion process, were cheaper to produce than daguerreotypes, which are silver-plated copper. But soon enough ambrotypes were overtaken by an even cheaper process, tintypes.

Tintypes are the subject of Janice G. Schimmelmann, who literally has written the book, i.e., The Tintype in America, 1856-1880. “Because of the tintype portrait, we have a visual record of post-1860 America -- vivid and direct,” she writes in her essay here. “Three Women Weeping” depicts mourners with what looks like a painted portrait of a man in their hands -- a deceased father or brother, Schimmelmann speculates. Their white handkerchiefs hide their faces. The young man pictured in “How Not to Be Seen” hides his face for a different reason and in a different way, with his hat tipped down over his eyes, as if he were napping standing up. Is he being funny or coy? “His battered hat, folded arms, and five-pointed star on his shirt only add to the mystery,” observes Schimmelmann, who has chosen these tintypes’ titles -- a creative act, as is the act of collecting. As she notes, “To add a tintype to my collection is a careful aesthetic choice.”

Other experts who share their collections in these pages include Greg French (daguerreotypes of outdoor scenes), Sabine Ocker (cyanotypes), Thomas Harris (cartes de visite), and Kenneth H. Rosen (early American stereoviews). Those unfamiliar with the depth and breadth of antique images will be amazed at what the photographic record shows.

French’s image of a shipbuilding scene includes a bed sheet hanging out a window. “So much for perfection, and yet it is perfect,” declares French, since the detail brings such an undeniably human moment literally into the picture. A farm scene of prize bulls is another gem from French, a collector-dealer, who has an instructive section on his Website, “A Beginner’s Primer: Ten Criteria for Evaluating Daguerreotypes.” In French’s astute analysis of the scene, the men’s poses demonstrate the power of animals in an agrarian society. In similar group portraits of men from different social classes, he writes, “there is usually a hierarchy where the well-heeled men in the top hats (presumably the owners) segregate themselves from their employees.” In this scene, however, “they are all incidental to the bulls.”

Ocker’s luminous Prussian blue cyanotype images range from a newly hatched chick to a man posing with his Penny Farthing bicycle to a Mount Holyoke chemistry student (class of 1898) in her lab. There is also a wonderful horizontal view of dozens of steamer trunks piled high at the Northampton, Massachusetts, train station. It’s from an album by an unknown member of Smith College’s class of 1905. As an historian of photography, Ocker has uncovered the distinctive role that cyanotypes played in women’s colleges and lives during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “The availability of cheap cameras and pre-coated papers created an explosion” in documentation by women, who sometimes marketed their images, Ocker writes. That’s what those young people were doing with their spare time.

Rosen’s chapter gives us stereoviews (three-dimensional when seen through a stereoscope) of buildings (Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, 1854), soldiers (Union men at a camp dinner), landscape vistas (Yosemite Falls, 1861, by Carleton Watkins), and celebrities (Mark Twain at his in-laws’ Quarry Farm in Elmira, New York). Young people and others who think 3-D movies are something new -- or, at the earliest, invented in the 1950s -- should be informed of the mid-19th-century technology that made possible these compelling images.

Some of the essayist-collectors share general thoughts about the art of collecting, useful to anyone who is object-obsessed. Most generous with his collecting philosophy is Mike Kessler, whose chapter is about stereoscopes. Kessler moved on to them after cameras and a host of other collecting interests, ordinary (stamps) and extraordinary (ice skates). What tipped the balance in favor of stereoscopes over cameras, he writes, was that “where countless reference books and price guides exist for cameras, the true extent of the field of stereoscopes isn’t fully known and may never be. There’s still the thrill of discovery.”

There’s so much more: magic lanterns and optical toys by Richard Balzer, autochromes by Hugh Tifft and Jeremy Rowe, and European daguerreotype stereoviews by the Ginnses. One from the Ginnses’ collection is a portrait of an unidentified man with a stereoscope and a lens on the table beside him. “For over twenty years, I have tried to ascertain the identification of the sitter,” Bryan Ginns writes. He has speculated that this could be an important person in the optical or photography field. Or “it could be just a creative French daguerreotypist using these instruments as studio props.” Undoubtedly, Bryan, like a true collector, will continue trying to solve the mystery.

All collecting interests needs to be awakened. I’m sure most collectors can recount their own collector “origin story,” i.e., their first encounter with whatever has become the center of their collecting lives. Many of them may wonder what they’d be doing now if not for that introduction. To be realistic, young people probably aren’t going to stumble upon this book. They’ll need to be shown it. However, there are far greater odds that they will serendipitously find antique photography on the Internet.

As it happens, the Ginnses operate the only online auction in the United States specifically handling the antique imagery and hardware of photography’s first 100 years. There are also numerous Websites on antique photographica that repay time spent with them. With the same phone that the young are using to take selfies, they can, for starters, take a look at Luminous Lint; Michael Pritchard’s British Photographic History; and the online American Museum of Photography. Once hooked, they’ll be searching for all the information they can find, only a tiny fraction of which is, still at this point, anywhere but between the pages of a book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed