Seen at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, last Friday afternoon, this piece of folk art (left) meant to stand in a parlor is, purportedly, a late nineteenth-century Civil War memorial. I say "purportedly" because, I found it impossible to look at it without harking back to the notorious Harold Gordon fake (above) -- a secretary-bookcase with clock -- that this same museum bought from dealer Allan Katz at the Winter Antiques Show in January 2015. Attributed to members of Connecticut’s 16th Infantry, it was said to have been made in 1876 to honor brothers Wells Bingham (1845–1904) and John Bingham (1844–1862), who had fought at Antietam. An article in the September 2015 issue of The Magazine Antiques said that on the opening night of the New York show, "senior leadership, curators, and trustees" from the museum "huddled excitedly" in front of it and arrived at an "immediate consensus: the Bingham secretary should return to Connecticut." The article also called it "a folk art masterpiece."

Unfortunately, three years after its purchase, it was called out -- with the help of my husband, who informed Clayton Pennington, editor of Maine Antique Digest, about the existence of before-and-after photos of it. Once confronted, Gordon confessed to having married an actual story with a fabricated "antique." But the sale, to a museum no less, should never have succeeded. When Clayton's story about it ran in M.A.D., someone very shortly wrote a letter to the editor saying it was easy to see at a glance that it wasn't authentic because the typeface used on the lettering was Times Roman--a font not invented until 1931. So much for the reliability of the vetting committee at the Winter Antiques Show, at least in that instance.

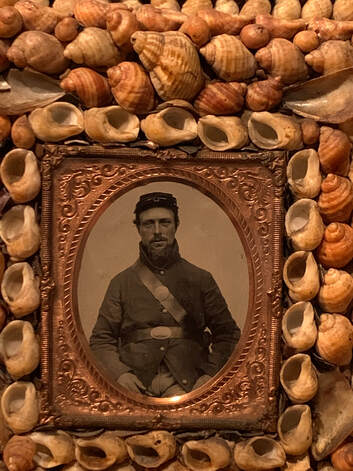

As for the seashell-encrusted Civil War memorial pictured above, it is attributed by the museum to Eliza Jane Turner Trask (1834-1919), who is said to have made it after the safe return of her husband, Adoniram Judson Trask (1833-1897), a member of the 21st Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The distraction of the Gordon fake aside, what interests me most about the piece, a refashioned candlestand, is the name of its honoree-husband. He seems to have been named after one of our earliest American foreign missionaries, Adoniram Judson (1788-1850), who has been among the subjects of my research for The Missionary Factory project over the last several years. The name would mean nothing to me otherwise, but it meant a lot to the nineteenth-century evangelicals who believed in the Rev. Judson's goal of saving the world for Christ. Trask's parents must have been among them. According to genealogy websites, they were Sally Haggett Trask (1800-1884) and the Rev. Enos S. Trask (1795-1880), minister of the Nobleboro Baptist Church in Nobleboro, Maine. How it got out of the family and into the museum would be a storyline worth pursuing. The label on the museum wall says only that it was a "Gift of H. Carl Cramer by exchange" in 1986. I did an internet search for information about Cramer, but came up only with someone by that name who was a contributor to scientific magazines in the period 1912-1913. I leave the project of finding out more about him to someone else; I have my own. Speaking of which, there is an underlying theme of this commentary of mine, the point, if you will, that relates both to the insufficiently questioned acceptance of a piece of fake furniture and to the religious conviction of nineteenth-century missionaries and their supporters. It can be expressed in a single, summing-up word: belief.

Unfortunately, three years after its purchase, it was called out -- with the help of my husband, who informed Clayton Pennington, editor of Maine Antique Digest, about the existence of before-and-after photos of it. Once confronted, Gordon confessed to having married an actual story with a fabricated "antique." But the sale, to a museum no less, should never have succeeded. When Clayton's story about it ran in M.A.D., someone very shortly wrote a letter to the editor saying it was easy to see at a glance that it wasn't authentic because the typeface used on the lettering was Times Roman--a font not invented until 1931. So much for the reliability of the vetting committee at the Winter Antiques Show, at least in that instance.

As for the seashell-encrusted Civil War memorial pictured above, it is attributed by the museum to Eliza Jane Turner Trask (1834-1919), who is said to have made it after the safe return of her husband, Adoniram Judson Trask (1833-1897), a member of the 21st Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The distraction of the Gordon fake aside, what interests me most about the piece, a refashioned candlestand, is the name of its honoree-husband. He seems to have been named after one of our earliest American foreign missionaries, Adoniram Judson (1788-1850), who has been among the subjects of my research for The Missionary Factory project over the last several years. The name would mean nothing to me otherwise, but it meant a lot to the nineteenth-century evangelicals who believed in the Rev. Judson's goal of saving the world for Christ. Trask's parents must have been among them. According to genealogy websites, they were Sally Haggett Trask (1800-1884) and the Rev. Enos S. Trask (1795-1880), minister of the Nobleboro Baptist Church in Nobleboro, Maine. How it got out of the family and into the museum would be a storyline worth pursuing. The label on the museum wall says only that it was a "Gift of H. Carl Cramer by exchange" in 1986. I did an internet search for information about Cramer, but came up only with someone by that name who was a contributor to scientific magazines in the period 1912-1913. I leave the project of finding out more about him to someone else; I have my own. Speaking of which, there is an underlying theme of this commentary of mine, the point, if you will, that relates both to the insufficiently questioned acceptance of a piece of fake furniture and to the religious conviction of nineteenth-century missionaries and their supporters. It can be expressed in a single, summing-up word: belief.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed