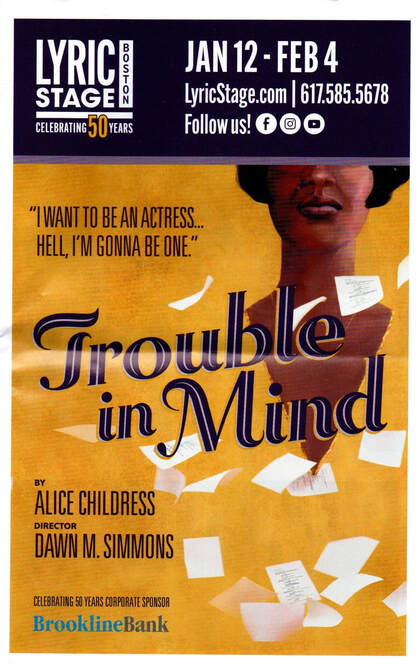

We decided a couple of weeks ago to celebrate Bob's 72nd birthday by going to see a play in Boston. Any play. We looked at what was available and chose one. Thank God we made the random choice that we did. Otherwise we would have missed Alice Childress's brilliant Trouble in Mind, presented by the Lyric Stage.

We went in cold, not knowing a thing about it, but the name Alice Childress (1912-1994) was familiar to me from the Printed and Manuscript African Americana sales at Swann that I wrote about for many years. At some point, I had come across her and some rare edition of one of her novels, probably A Hero Aint Nothin' But a Sandwich. But that's as far as my knowledge went. I didn't even know that the play's title was taken from that of a famous blues song. In any case, into Boston we drove on a snowy afternoon.

The play's premise is that its African American cast was going to have to perform as stereotypes in yet another tiresome, third-rate production. Taking on the roles of characters named "Petunia" and "Ruby," the women were going to have to do the usual shouting of things like "Lawd have mercy!" and one of men was going to have to do such a loathsome thing as whittle a stick. And in the beginning scenes, although they made hilarious fun of the whole enterprise, they were, as always, willing to comply because they wanted to be actors in anything and they needed the money.

As the play proceeds, however, "Ruby," a.k.a. Wiletta, finds she has had enough of it. The play-within-the-play's plot requires her to deliver her son, who has committed the terrible crime of voting, into the hands of the local sheriff for his own, supposed safety. She argues with the director, a white man named Al Manners, asserting that a mother would never give up her son like that. She would urge him to escape. She refuses to practice the scene and insists that it be changed. The other cast members, because they really do need their jobs, don't support her. She is a lone voice, which delivers an amazing monologue, asking Al Manners over and over if he would give his own son up to a sheriff and, it is understood, certain death. Manners then delivers his own monologue, culminating in the admission that he would never equate his white son with any son of a black woman.

The play had a run Off Broadway in 1955, but never made it to Broadway itself, until 2021, because Childress refused to rewrite it to be more acceptable to white audiences. She was just like her own character, Wileta, in that -- refusing to compromise and accepting the consequences.

Addendum: To wit: “Once Upon a Time, Again,” a review of James by Percival Everett (a retelling of Huckleberry Finn from Jim's point of view) in The Economist, March 16, 2024, 72-73: “Jim decides to indulge them anyway—because ‘it always pays to give white folks what they want.’” “In Mr. Everett’s telling, Jim’s slave dialect is a put-on. He drops it around other slaves, but reverts to [it] when a white person appears. ‘White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them.’” The book is on my to-read list. -- J.S. April 30, 2024.

We went in cold, not knowing a thing about it, but the name Alice Childress (1912-1994) was familiar to me from the Printed and Manuscript African Americana sales at Swann that I wrote about for many years. At some point, I had come across her and some rare edition of one of her novels, probably A Hero Aint Nothin' But a Sandwich. But that's as far as my knowledge went. I didn't even know that the play's title was taken from that of a famous blues song. In any case, into Boston we drove on a snowy afternoon.

The play's premise is that its African American cast was going to have to perform as stereotypes in yet another tiresome, third-rate production. Taking on the roles of characters named "Petunia" and "Ruby," the women were going to have to do the usual shouting of things like "Lawd have mercy!" and one of men was going to have to do such a loathsome thing as whittle a stick. And in the beginning scenes, although they made hilarious fun of the whole enterprise, they were, as always, willing to comply because they wanted to be actors in anything and they needed the money.

As the play proceeds, however, "Ruby," a.k.a. Wiletta, finds she has had enough of it. The play-within-the-play's plot requires her to deliver her son, who has committed the terrible crime of voting, into the hands of the local sheriff for his own, supposed safety. She argues with the director, a white man named Al Manners, asserting that a mother would never give up her son like that. She would urge him to escape. She refuses to practice the scene and insists that it be changed. The other cast members, because they really do need their jobs, don't support her. She is a lone voice, which delivers an amazing monologue, asking Al Manners over and over if he would give his own son up to a sheriff and, it is understood, certain death. Manners then delivers his own monologue, culminating in the admission that he would never equate his white son with any son of a black woman.

The play had a run Off Broadway in 1955, but never made it to Broadway itself, until 2021, because Childress refused to rewrite it to be more acceptable to white audiences. She was just like her own character, Wileta, in that -- refusing to compromise and accepting the consequences.

Addendum: To wit: “Once Upon a Time, Again,” a review of James by Percival Everett (a retelling of Huckleberry Finn from Jim's point of view) in The Economist, March 16, 2024, 72-73: “Jim decides to indulge them anyway—because ‘it always pays to give white folks what they want.’” “In Mr. Everett’s telling, Jim’s slave dialect is a put-on. He drops it around other slaves, but reverts to [it] when a white person appears. ‘White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them.’” The book is on my to-read list. -- J.S. April 30, 2024.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed