It's fairly well known here in Andover, Massachusetts, although not elsewhere, that Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) lived in town from 1852 through 1864. Mrs. Stowe is remembered with a memorial plaque on the house, a stone structure that has since been moved, but which is still not far from where she is buried. The gravesite is in Phillips Academy's cemetery. Her husband, Calvin Ellis Stowe (1802-1886), is buried there, too, as is her son Henry (1838-1857), who drowned while a student at Dartmouth College. When Mrs. Stowe arrived in Andover, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was about to be published in book form after having been serialized in an abolitionist periodical for many weeks. Mr. Stowe, a Bible scholar, had been hired by Andover Theological Seminary, which shared a campus with P.A., to teach courses on "sacred literature." Both Frederick Douglass and "an old colored woman, a kind of prophetess, called Sojourner Truth" visited Mrs. Stowe in that house one day in 1860, according to The Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, written by another son of hers, Charles Edward Stowe (!850-1934). Sacred ground, indeed.

When, however, I read Charles Johnson’s introduction to Uncle Tom’s Cabin not long ago, I was reminded of how African Americans feel about Uncle Tom. In Mr. Johnson's words, Mrs. Stowe's characterizations simply replace "one racist stereotype with another that is equally condescending and unacceptable.” Considering "western, white humanity’s painfully slow progress toward social enlightenment," Mr. Johnson avers, "Stowe’s now-embarrassing, unfortunately toxic racial thinking is a small step forward, from hatred and negrophobia to a blatant paternalism that was used soon enough to rationalize colonialism and, we must admit, exists to this very day.” And so, he concludes, “Stowe’s book challenges us ... to ask whether it is possible ever to write well the lived experience of the racial Other."

I understand what he is saying, of course, and I agree with it. And yet I cannot change the contradictory fact that a book written about “Negroes” by a white man began my education about the prejudices I myself once harbored. Like the Rogers & Hammerstein song “You’ve Got To Be Carefully Taught,” my erroneous ideas were a parental legacy. As the sixties progressed and I matured, my mind began to open, but I still lacked the kind of education that is the antidote to ignorance. Then in 1969 I went to college in Washington, D.C., and shortly chose to take a course in local history, one of whose assigned texts was Elliot Liebow's Tally’s Corner. The summer before I left for college, I had read Claude Brown's Manchild in the Promised Land, a fictionalization of his boyhood in Harlem. And although that book had a big impact on me, it wasn't nearly as important to my personal growth and enlightenment as Liebow's now classic work.

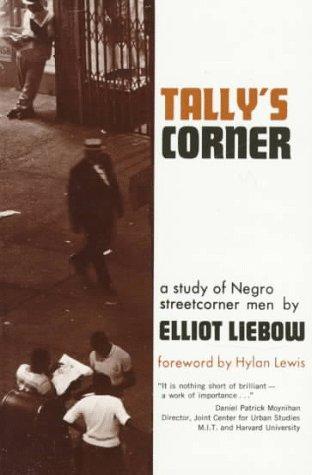

Tally's Corner, subtitled A Study of Negro Streetcorner Men, was published by Little, Brown in 1967 and has since sold more than one million copies. It was originally written by Liebow as a Ph.D. dissertation in anthropology for the Catholic University of America. He collected most of his data between January 1962 and July 1963 while doing "field work" for a research project, "Child Rearing Practices Among Low Income Families in the District of Columbia," during which he was required to collect information about adult men. His subjects, all given pseudonyms, consisted of about two dozen subjects who frequented the New Deal Carry-out. He recorded their daily activities there and "in the alleys, hallways, poolrooms, beer joints, and private houses in the immediate neighborhood." His investigation extended to "courtrooms, jails, hospital, dance halls, beaches and private houses elsewhere in Washington and in Maryland and Virginia." Going into it, he had no thesis to prove, no argument to make, and he didn't conduct formal "interviews." He analyzed and wrote only afterwards. What is more, he said, there was no attempt to describe "any Negro men other than those I was in direct, immediate association."

Those men were the pseudonymous Tally, Sea Cat, Leroy, and so on, nicknamed or otherwise They were ages 21 to 44. They were laborers, janitors, busboy-dishwashers, truck drivers, retail clerks, and unemployed. Some worked nights; that's why they appeared to be jobless when hanging out on the street corner during the day. Others didn't want a job, at least not the kind being offered, consisting of "scuffling day and night" for below living wages or too physically demanding for their ill or disabled bodies. "Delivering little, and promising no more, the job [for the men of Tally's Corner] is 'no big thing,'" Liebow reported. They acquired their prestige in other ways. And so on, through chapters that address and illuminate the men's relationships with their children, with women, and with each other.

Liebow (1925-1994) wrote an appendix in which he said he felt comfortable working in the milieu of the street corner. He had been raised in D.C. by Jewish immigrant parents. His father was a grocer; they lived above the store. The schools he attended were white, but all of the store's customers and most of the Liebows' neighbors were black or, as he put it in the language of the era, "Negroes." Still, he knew he was an outsider and always would be, not only because of his race but because of his "occupation, education, residence, and speech." The fact that he was Jewish came up only twice. As Liebow tells it: "Once, a man who worked but did not live in the area threw some Yiddish expressions at me because 'I thought you looked Jewish.' The other time was when I met a soldier in a local bootleg joint. We had been talking for some ten minutes or so when he asked me whether I was 'Eyetalian.' I told him I was Jewish. 'That's just as good,' he said. 'I'm glad you're not white.'"

To be continued.

When, however, I read Charles Johnson’s introduction to Uncle Tom’s Cabin not long ago, I was reminded of how African Americans feel about Uncle Tom. In Mr. Johnson's words, Mrs. Stowe's characterizations simply replace "one racist stereotype with another that is equally condescending and unacceptable.” Considering "western, white humanity’s painfully slow progress toward social enlightenment," Mr. Johnson avers, "Stowe’s now-embarrassing, unfortunately toxic racial thinking is a small step forward, from hatred and negrophobia to a blatant paternalism that was used soon enough to rationalize colonialism and, we must admit, exists to this very day.” And so, he concludes, “Stowe’s book challenges us ... to ask whether it is possible ever to write well the lived experience of the racial Other."

I understand what he is saying, of course, and I agree with it. And yet I cannot change the contradictory fact that a book written about “Negroes” by a white man began my education about the prejudices I myself once harbored. Like the Rogers & Hammerstein song “You’ve Got To Be Carefully Taught,” my erroneous ideas were a parental legacy. As the sixties progressed and I matured, my mind began to open, but I still lacked the kind of education that is the antidote to ignorance. Then in 1969 I went to college in Washington, D.C., and shortly chose to take a course in local history, one of whose assigned texts was Elliot Liebow's Tally’s Corner. The summer before I left for college, I had read Claude Brown's Manchild in the Promised Land, a fictionalization of his boyhood in Harlem. And although that book had a big impact on me, it wasn't nearly as important to my personal growth and enlightenment as Liebow's now classic work.

Tally's Corner, subtitled A Study of Negro Streetcorner Men, was published by Little, Brown in 1967 and has since sold more than one million copies. It was originally written by Liebow as a Ph.D. dissertation in anthropology for the Catholic University of America. He collected most of his data between January 1962 and July 1963 while doing "field work" for a research project, "Child Rearing Practices Among Low Income Families in the District of Columbia," during which he was required to collect information about adult men. His subjects, all given pseudonyms, consisted of about two dozen subjects who frequented the New Deal Carry-out. He recorded their daily activities there and "in the alleys, hallways, poolrooms, beer joints, and private houses in the immediate neighborhood." His investigation extended to "courtrooms, jails, hospital, dance halls, beaches and private houses elsewhere in Washington and in Maryland and Virginia." Going into it, he had no thesis to prove, no argument to make, and he didn't conduct formal "interviews." He analyzed and wrote only afterwards. What is more, he said, there was no attempt to describe "any Negro men other than those I was in direct, immediate association."

Those men were the pseudonymous Tally, Sea Cat, Leroy, and so on, nicknamed or otherwise They were ages 21 to 44. They were laborers, janitors, busboy-dishwashers, truck drivers, retail clerks, and unemployed. Some worked nights; that's why they appeared to be jobless when hanging out on the street corner during the day. Others didn't want a job, at least not the kind being offered, consisting of "scuffling day and night" for below living wages or too physically demanding for their ill or disabled bodies. "Delivering little, and promising no more, the job [for the men of Tally's Corner] is 'no big thing,'" Liebow reported. They acquired their prestige in other ways. And so on, through chapters that address and illuminate the men's relationships with their children, with women, and with each other.

Liebow (1925-1994) wrote an appendix in which he said he felt comfortable working in the milieu of the street corner. He had been raised in D.C. by Jewish immigrant parents. His father was a grocer; they lived above the store. The schools he attended were white, but all of the store's customers and most of the Liebows' neighbors were black or, as he put it in the language of the era, "Negroes." Still, he knew he was an outsider and always would be, not only because of his race but because of his "occupation, education, residence, and speech." The fact that he was Jewish came up only twice. As Liebow tells it: "Once, a man who worked but did not live in the area threw some Yiddish expressions at me because 'I thought you looked Jewish.' The other time was when I met a soldier in a local bootleg joint. We had been talking for some ten minutes or so when he asked me whether I was 'Eyetalian.' I told him I was Jewish. 'That's just as good,' he said. 'I'm glad you're not white.'"

To be continued.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed