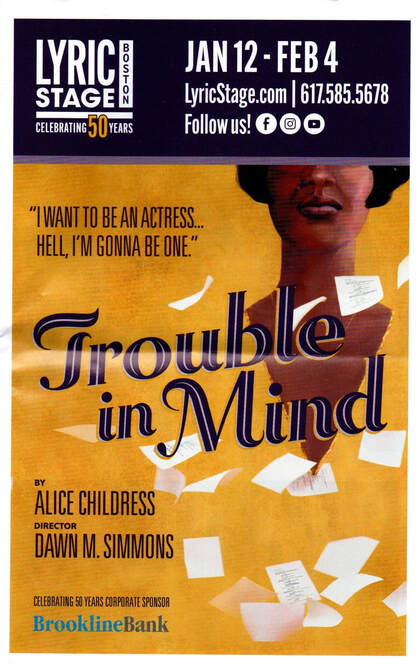

We decided a couple of weeks ago to celebrate Bob's 72nd birthday by going to see a play in Boston. Any play. We looked at what was available and chose one. Thank God we made the random choice that we did. Otherwise we would have missed Alice Childress's brilliant Trouble in Mind, presented by the Lyric Stage.

We went in cold, not knowing a thing about it, but the name Alice Childress (1912-1994) was familiar to me from the Printed and Manuscript African Americana sales at Swann that I wrote about for many years. At some point, I had come across her and some rare edition of one of her novels, probably A Hero Aint Nothin' But a Sandwich. But that's as far as my knowledge went. I didn't even know that the play's title was taken from that of a famous blues song. In any case, into Boston we drove on a snowy afternoon. The play's premise is that its African American cast was going to have to perform as stereotypes in yet another tiresome, third-rate production. Taking on the roles of characters named "Petunia" and "Ruby," the women were going to have to do the usual shouting of things like "Lawd have mercy!" and one of men was going to have to do such a loathsome thing as whittle a stick. And in the beginning scenes, although they made hilarious fun of the whole enterprise, they were, as always, willing to comply because they wanted to be actors in anything and they needed the money. As the play proceeds, however, "Ruby," a.k.a. Wiletta, finds she has had enough of it. The play-within-the-play's plot requires her to deliver her son, who has committed the terrible crime of voting, into the hands of the local sheriff for his own, supposed safety. She argues with the director, a white man named Al Manners, asserting that a mother would never give up her son like that. She would urge him to escape. She refuses to practice the scene and insists that it be changed. The other cast members, because they really do need their jobs, don't support her. She is a lone voice, which delivers an amazing monologue, asking Al Manners over and over if he would give his own son up to a sheriff and, it is understood, certain death. Manners then delivers his own monologue, culminating in the admission that he would never equate his white son with any son of a black woman. The play had a run Off Broadway in 1955, but never made it to Broadway itself, until 2021, because Childress refused to rewrite it to be more acceptable to white audiences. She was just like her own character, Wileta, in that -- refusing to compromise and accepting the consequences. We've been married now for fifty years. The anniversary was December 22, 2023. For a long while, I thought about writing an essay to commemorate the occasion. In the end, I decided instead on a short commentary, posted here, about the wedding presents I still have half a century after they were given to us.

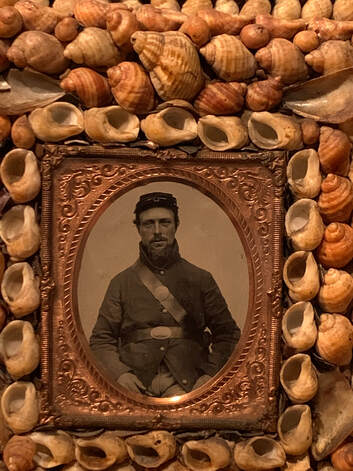

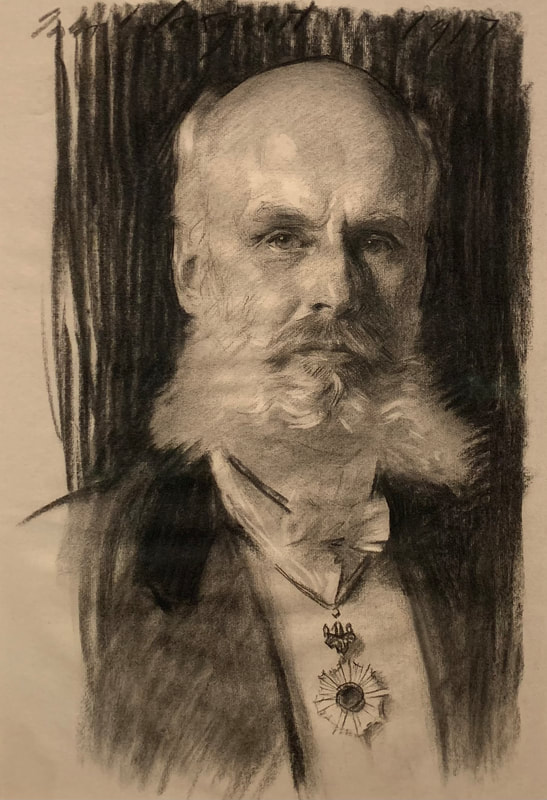

The wedding, in our D.C. apartment, was tiny, especially by today's standards: fourteen people including us, our parents, our siblings, their spouses, and the Jesuit friend who performed the ceremony. He said we should go to city hall and repeat it for the official record because he hadn't married us according to the laws of his faith and that was the requirement for it to be considered legal. We never did. I guess by now it's as official as it will ever be. My mother did send out what Bob's brother Steve referred to as a shake-down card, meaning it was an announcement designed to solicit gifts for us. I'm not sure how many she sent out and I don't think that was her intent. Even so, my Aunt Fanny, famously, said she would give us her gift when we visited her. That's another thing we never did. Anyway, the gifts that remain are few. A little knife. A very large stock pot. A set of stainless steel mixing bowls. And a silver-plated ice bucket. They're all items related to food and drink, as it happens, useful and, by now, looking very well used, especially the little knife, but not especially the ice bucket, which has come out only for parties. And actually the little knife was inside the stock pot -- it came from the same couple -- so I guess the number of gifts that remain numbers just three. The couple who gave us the knife-cum-stock pot, Martin and Marsha, got divorced shortly after they (or, probably, Marsha alone, since she, being the woman, was probably the gift-getter) chose that excellent combo. Sandi and Mark, the couple who gave us the terrific mixing bowls, split up too. As for the couple, Judy and Mo, who gave us the ice bucket, which was very stylish, like themselves, they never were married, although Judy thought they were going to be. The trouble was, even though they were engaged and a date had been set, Mo had neglected to get a divorce. Judy discovered that towards the end of their wedding preparations, when Mo was required to produce the divorce papers for the priest. We could hear Judy, who was our downstairs neighbor, crying for days; a few weeks or months later, I can't quite remember which, she packed up and drove back home to Wisconsin, leaving her cat, Saki, with us. Our Jesuit friend, Jeff Donnelly, by the way, didn't keep his vows, either. But that was probably a good thing. We saw him many years later, in Miami. After he'd left the priesthood, he got married -- to a former nun. So why have we remained married and very happily at that? We have our pat answers, which we voice now and again, when asked, but here, I'll just say that one reason for the longevity is because I never wrote much about our marriage through my equally long writing career. I think I'll keep it that way.  Seen at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, last Friday afternoon, this piece of folk art (left) meant to stand in a parlor is, purportedly, a late nineteenth-century Civil War memorial. I say "purportedly" because, I found it impossible to look at it without harking back to the notorious Harold Gordon fake (above) -- a secretary-bookcase with clock -- that this same museum bought from dealer Allan Katz at the Winter Antiques Show in January 2015. Attributed to members of Connecticut’s 16th Infantry, it was said to have been made in 1876 to honor brothers Wells Bingham (1845–1904) and John Bingham (1844–1862), who had fought at Antietam. An article in the September 2015 issue of The Magazine Antiques said that on the opening night of the New York show, "senior leadership, curators, and trustees" from the museum "huddled excitedly" in front of it and arrived at an "immediate consensus: the Bingham secretary should return to Connecticut." The article also called it "a folk art masterpiece." Unfortunately, three years after its purchase, it was called out -- with the help of my husband, who informed Clayton Pennington, editor of Maine Antique Digest, about the existence of before-and-after photos of it. Once confronted, Gordon confessed to having married an actual story with a fabricated "antique." But the sale, to a museum no less, should never have succeeded. When Clayton's story about it ran in M.A.D., someone very shortly wrote a letter to the editor saying it was easy to see at a glance that it wasn't authentic because the typeface used on the lettering was Times Roman--a font not invented until 1931. So much for the reliability of the vetting committee at the Winter Antiques Show, at least in that instance. As for the seashell-encrusted Civil War memorial pictured above, it is attributed by the museum to Eliza Jane Turner Trask (1834-1919), who is said to have made it after the safe return of her husband, Adoniram Judson Trask (1833-1897), a member of the 21st Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The distraction of the Gordon fake aside, what interests me most about the piece, a refashioned candlestand, is the name of its honoree-husband. He seems to have been named after one of our earliest American foreign missionaries, Adoniram Judson (1788-1850), who has been among the subjects of my research for The Missionary Factory project over the last several years. The name would mean nothing to me otherwise, but it meant a lot to the nineteenth-century evangelicals who believed in the Rev. Judson's goal of saving the world for Christ. Trask's parents must have been among them. According to genealogy websites, they were Sally Haggett Trask (1800-1884) and the Rev. Enos S. Trask (1795-1880), minister of the Nobleboro Baptist Church in Nobleboro, Maine. How it got out of the family and into the museum would be a storyline worth pursuing. The label on the museum wall says only that it was a "Gift of H. Carl Cramer by exchange" in 1986. I did an internet search for information about Cramer, but came up only with someone by that name who was a contributor to scientific magazines in the period 1912-1913. I leave the project of finding out more about him to someone else; I have my own. Speaking of which, there is an underlying theme of this commentary of mine, the point, if you will, that relates both to the insufficiently questioned acceptance of a piece of fake furniture and to the religious conviction of nineteenth-century missionaries and their supporters. It can be expressed in a single, summing-up word: belief. I think just a little bit more should have been made of William Sturgis Bigelow (1850-1926) at the MFA Boston's new exhibit of Hokusai woodblock prints and their outsized influence on the world of art. He was the one who collected most of the Hokusai examples that are in the MFA's collection. The exhibit does have a 1917 charcoal sketch of him, in which he is wearing his medal from Japan's Order of the Rising Sun. The artist: John Singer Sargent.

Bob took this photo of me c. 1979-1980, when we lived at 535 11th Street SE on Capitol Hill in D.C. I remember joking that it would make a good author photo. I wonder what book I'm leaning against. I also wonder if I thought back then that I actually would publish a book of my own. The first one, Shadow Bands, didn't come out until 1988... We rediscovered this image while Bob was getting ready to donate to the archives at George Washington University some of the photos he took in his college dorm room in the period 1969-1971. He still had the contact sheets and negatives, and remembered many of his fellow students' names. Great period posters are on the walls. Our wish is that they will make good research materials for someone studying those times, which were not routinely documented in the way that smart-phone-wielding students document themselves today.

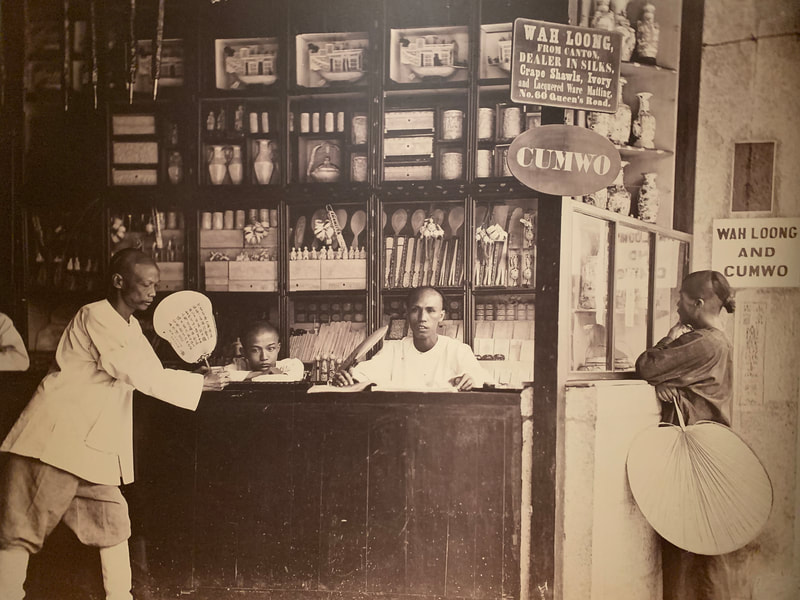

I went to see Power & Perspective: Early Photography in China, at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, last week. It is an excellent exhibition of images of China and its people in the 19th century, mostly by visiting Europeans. And they do bring their Western colonial bias to the material (hence, the organizers' title), but they cannot distort the beauty of the landscape and of the Chinese people who posed for them. On the far left, a Queen's Road Curio Shop in Hong Kong, c. 1868-1872 by John Thomson, a Scotsman, who published books of his images. In the middle, The Island Pagoda, from Thomson's book Foochow and the River Min. (On right, husband Bob, my faithful museum companion.) Below, the tombstone of St. Francis Xavier, the sixteenth-century missionary who co-founded the Jesuits. It's by Marciano Antonio Baptista, who was born to a Portuguese Macau family and mainly was a painter. The grave is in Shangchuan; the photo dates from either 1864 or 1868. And it's certainly not one of the best images in the show, but it caught my attention, since it relates to my current long-term project, The Missionary Factory (see www.themissionaryfactory.com).

I saw the Central Square Theater's production of Lloyd Suh's The Chinese Lady on Wednesday night. It is the story of Afong May, who is brought from China to the United States at age fourteen in 1834 and put on display in a forerunner of P.T. Barnum's museum and later in the Barnum museum itself. She doesn't quite understand what is happening to her, but gradually as the years go by, she realizes her situation, especially when, at age forty-four, she is about to be replaced, since, as we told, freshly arrived is a new fourteen-year-old cultural curiosity from the Far East. Americans marvel at how Afong May walks in her bound feet, how she eats her rice and shrimp with chopsticks, and how she comports herself in general -- prissily. There is of course a language barrier, but she has a translator and attendant, a Chinese man, Atung, who, as becomes clear when he delivers his monologue, is suppressing his rage at his own situation. The production could have used better staging, although I understand the financial straits of such a small community theater. I think, too, that Sophori Ngin, who plays Afong May, should have shown more change as the years go by. The sameness may have been the result of a directorial decision, but if so, I think it was an unfortunate one. Atung, played by Jae Woo, expresses a much wider range. Through his varied mannerisms, posture, stance, voice, and gait, I saw and felt his exasperation (at the immature and gullible teenaged Afong May), his lust (for her when she becomes a woman), his anger (at the world that treats him as "irrelevant" at best), and his grief (when Afong May's departure is imminent). Woo also conjures a perfect, cringe-worthy President Andrew Jackson when Afong meets him in Washington, D.C., while she is on a multi-city tour. It's a virtuosic set piece. I wish there were more of them. As it stands, the play is worthy of our attention. I don't think I have finished thinking about it. |

AuthorThe "Commentaries" portion of this website is a record of some of Ms. Schinto's cultural experiences, e.g., books read, TV series watched, movies seen, exhibits visited, plays and musical events attended, etc. She also from time to time will post short essays on various topics. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed